Making Cities Work: Mexico City

Dejan Sudjic - BBC News Dejan Sudjic - BBC News

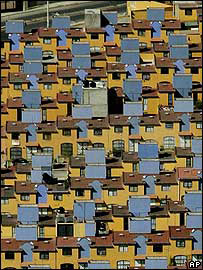

| | Mexico City's housing boom has transformed parts of the city. |

All the cliches about Mexico City are true.

It is a sprawling metropolis of 19 million people, the second-largest city in the world, where 40% of the people live below the poverty line.

This is a place of homeless street kids, piracy, pollution, crime, and 100,000 street vendors.

At the same time, the rich live in a world of gated communities, rooftop swimming pools, and commuting by helicopter.

But it is also a city that has stepped back from the brink of disaster, and wants to become more liveable.

Family needs

The international Urban Age conference, which is about improving urban life, recently brought experts from across the globe to share ideas on how to help improve Mexico City.

The country's capital is polluted, and water is in short supply.

A third of its people live in shanty towns with no basic services.

Adding to the problems is the fact that roughly half of the area falls within the City, while half classed as in the state of Mexico - meaning decisions have to be taken on different levels, often between representatives of opposing parties.

"There are great efforts being done - but they are not radical enough," said architect Enrique Norton.

"In order to get this place liveable, we need to really bring life to it - we need to attract institutions and people that have left."

"They need to be able to come back and find a Class A quality of life. If not, painting the facades and cleaning the streets won't do it."

He added that crucially, he believes Mexicans need to begin building up - in the form of tower blocks - rather than simply further and further outwards, which creates the need for more roads and sewer lines.

"All the families that live in a certain area could live in a beautiful tower, with a great garden and a great pool," he said.

"The density will bring security, more services, more businesses. We can see that in any city. People in New York and Tokyo live in very small spaces, but they have a great opportunity to leave the city."

"But here, people live in very small spaces and have no public space. The city gives them nothing."

However, Sarah Toppleson, of the Mexican Centre for Housing Research, said this is not how the city's population likes to live.

"Generally, people don't like to live in apartments, because Mexico as a society tends to include our family," she explained.

"If a brother is not doing very well, you bring him home to live with you. But if you have a little house, you can always build an extra room."

"If your father dies, you can bring your mother in - and again, you need another room. I don't think we should break those ties - but if we go to apartments, we should have apartments of different sizes."

"We need to create new ways of listening to the needs of our families in Mexico."

Tipping point

Another sure way to regenerate the city centre is through the care of public space.

This has happened around the world, from Bogota to Barcelona, so why not here?

"There are issues like pollution, traffic, and recently insecurity," explains Mexican novelist Guillermo Sheridan. "Many areas have already been abandoned, because they have been taken over by other forces."

The theory is that at least 40% of the economy in the city is informal - people who do not pay taxes, and who make a living based on selling small amounts of things, from children's books to luminous stars.

But the tipping point comes when the street life turns whole parts of the city into no-go areas.

"It's now overrun with vendors selling pornography, and nobody does anything about that," said Sheridan.

Though he still lives in one of the more engaging parts of the city, Sheridan remains its sternest critic.

"The moral temperature of the city has gone completely out of control," he said.

"There are no laws to be obeyed any more... the city is strangling its inhabitants, and condemning them to complete isolation."

As a result, many of those who can afford to do so are choosing such isolation for themselves - in gated communities like Bosque de Santa Fe.

These places are not just for the rich any more - the middle classes live there too, a sign that communities are turning in on themselves.

"We have a better life here," said Luicila La.

"We have time, we are not in traffic all the time, we have trees and a nice place."

Hope

But others fear this works against the essential goal of social integration.

Gitan Tuwari, of the Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi - known for clear thinking about transport - sees parallels with old South Africa, believing Mexico City is creating a "well-structured apartheid system."

"These kind of gated communities remind me very much of that," she said.

Ironically, according to the latest research, socially mixed communities are more secure for everyone.

Ricky Burdett, a professor in architecture and urbanism at the London School of Economics, said that when New York turned itself around in the 1990s - and dramatically cut crime - it was partially due to "intense immigration" of Koreans and Chinese, and the mixing of people that resulted.

"They had no truck with the local mafia, the dealings of gangs or anything else, and the positive impact of this migration has had more of an impact on reducing crime," he said.

And, in Mexico City, he believes there are signs of a brighter future.

Recently, Mexico's housing boom has seen clean, white houses spring up in the midst of smaller, grubbier ones, the informal settlements which house the poor.

"It's that proximity which will breed a level of integration which will maintain the extraordinary vibrancy of a place like Mexico City," he said.

Dejan Sudjic is the Guardian's architecture critic. |