For a Change, Builders from La Jolla, New Homes in Tijuana

Emily Alpert - Voice of San Diego Emily Alpert - Voice of San Diego

go to original

|

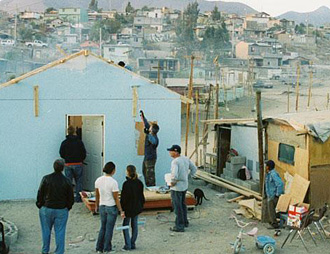

Click image to enlarge | | In a single day, teen volunteers erect a basic home to replace the shack, right, where Carla Ortega Rodriguez, her husband Jose Ignacio Rojas Reyes and their three-year-old daughter Ashley live. (Emily Alpert) |

SUVs sporting stickers from La Jolla and Del Mar trundle slowly down the dirt roads, a commotion of dust rising around them. Teens in La Jolla High sweatshirts and UCSD t-shirts peer out the windows at the haphazard shanties strung along the railroad tracks, patchwork homes of scrap wood, billboards, and discarded garage doors that house toddling children who run to greet the cars, waving.

To the La Jolla High students ferried here to build homes, the squatters' camp called Villa del Tren looks like the Third World. To residents who migrated here from Mexico's interior, it represents opportunities unheard of elsewhere in Mexico: a chance to own a plot of land, to educate your children.

Those realities collided Saturday east of Tijuana, where 22 service-minded students from one of San Diego's posh enclaves spent a day hammering together two homes for Mexican families in Villa del Tren. The initiative, Project Mercy, brings groups south from San Diego to build simple single-family houses. A crew of one dozen can build a home in a day. With 22 students and a handful of adults, this group is trying for two.

"I've come down a lot to Baja Malibu (to surf)," says Colburn Mowry, a La Jolla High sophomore. This was his first Project Mercy trip; other students had visited Villa del Tren last year. "But I've never done anything quite like this. It's crazy. Living in La Jolla, you never expect to see this kind of stuff."

Carla Ortega Rodriguez cradles her 3-year-old daughter Ashley and watches as the teens are divvied into crews. Her husband, Jose Ignacio Rojas Reyes, labors alongside them, lifting the wooden walls into place. They take orders from Alfredo d'Escragnolle, a Project Mercy board member who darts between the two adjacent worksites, guiding the fresh-faced builders. He clucks at a teen girl who brought a dainty jeweler's hammer to work.

"You need a real hammer!" he exclaims. "Schwarzenegger size! Let's move, they need this house today. Look at the conditions that they're living in."

Opposite Rodriguez, Alicia Valenzuela Soto doles out fruit snacks to her 11-year-old son, Jesus Daniel, in her shack, a single room that barely fits a mattress, a dented table and the stove. Three-year-old Leslie clambers on a homemade rope swing, just inside the door; her baby brother Aaron coos from the bed. Flies linger around his lips. When it rains, Soto said, water slips between the "Made in Korea" plastic sacks strewn over the roof, muddying the floor.

Her family's new home "means so much. So much," Soto said in Spanish.

Project Mercy was founded by Paula Claussen, a San Diego travel agent who visited Tijuana's slums with a friend to deliver clothing, and decided homes were a bigger need. The nonprofit works with communities to identify their neediest families, hires local journeymen to pour concrete foundations, then imports volunteer laborers to build the homes.

Each home costs roughly $3,200 to build, paid for by foundations and private donors. The simple houses lack plumbing, Claussen says, but they keep heat in, and scorpions out. She estimates that Project Mercy has built 1,000 such homes.

Until recently, Project Mercy didn't extend into Villa del Tren. The nonprofit only helps families who have legal title to their land - or who are trying to get it. Without it, Claussen fears the hard-won houses could be demolished. Settlements like Villa del Tren are often illegal, built on private or government land without permission. Often, a single organizer "rents" building space to families, who erect makeshift homes - space the organizer doesn't own.

"They are some of the neediest people I've seen," Claussen says. "We've wanted to help them for a long time, and couldn't, because they weren't there legally. The need is everywhere you look."

The makeshift neighborhoods, known as invasions, have sprung up as Mexicans migrate into Tijuana seeking work, says Antonio Zazueta, vice president of sales and marketing for Grupo Lagza, a land development company. Tijuana's population ticks upward 9 percent each year as Mexicans move into Tijuana from elsewhere, and development hasn't kept pace with the demand, Zazueta says. Meanwhile, rents are prodded upward by U.S. buyers, snapping up coastal properties just south of the border.

Despite the squalor, the makeshift neighborhoods represent opportunity to migrants, Zazueta says. Many have won formal recognition from the Mexican government, allowing renters to actually own their land, and eventually attracting basic utilities such as electricity and water to the impromptu communities. Here, jobs are plentiful in factories and construction sites, and children can go to school.

Villa del Tren is still negotiating with the railroad for the right to its land, says community leader Ruben Dario Rojas. Four years after families first settled here, it's still an "invasion," as the settlements are dubbed in Spanish. Neighbors tap electricity illegally from others' power lines. There are no sewers.

A cherubic boy named Jesus points across the hills, to a cluster of faraway men.

"Those are gangsters," says the boy, who wants to be a bus driver, and claims he doesn't know his age. "They come with knives and pistols." He draws his finger across his throat, then points up at a truck, lumbering into the valley "And that's the truck that brings milk."

Neighbor Ermelinda Rojas surveys the two homes rising from the concrete, the carloads of toys and clothing being divided among mothers and children. Her face glows.

"We are fighting for these people," Rojas says in Spanish. "We're negotiating to buy our land. Meanwhile, the little houses we have are very cold, and the little children get sick. We say, 'Thank God this program has started.'"

To the La Jolla teens, the poverty is stark, but not entirely a surprise. Most are members of Interact, a community service club sponsored by Rotary Club of La Jolla. They're not your average La Jolla teens, says the club's spokesperson, La Jolla High sophomore Itto Kabbage, who sums up her school as a mixture of surfers and professors' kids. Only 15 percent of its students were considered low-income in 2006, ranking it 30th among 32 San Diego high schools in percentage of low-income students.

"We have all the La Jolla stereotypes. ... There's no substance," Kabbage says, then concedes: "I guess it's like any other high school."

Kabbage compares the shantytowns to slums in Morocco, which she's visited with her French-Moroccan father. Freshman Roger Li likens them to China, where he's traveled several times before. For Sofia Vidali, a Mexican-American sophomore at the Bishop's School, they need no comparison.

"Because I'm Mexican, I know what we go through," says Vidali, who joined the project through her father Carlos, a Rotary Club member. "It's horrible. ... I don't think it's fair for people to live like this at all."

As workmen begin to frame the roofs, her father watches her with the other teens, playing a chaotic game of soccer with the Tijuana kids on a dirt road. Between tasks, the teens flock to the kids, and the kids to them.

"It's a good eye-opener for these teens," Carlos Vidali says. "And this is not the worst. There are worse places."

As the sky goes golden, the teens rush to finish the work, rolling sky-blue paint onto the walls. Alongside them, a posse of Spanish-speaking kids builds toy houses out of scrap wood blocks, and begs to borrow paint. But soon the sun has fallen, and the roofs are left for local workers paid by Project Mercy to complete the next day.

Sweaty and exhausted, the teens say their day in Villa del Tren gives them pause, and highlights their privilege. The bigger questions - the whys and hows - remain to be asked, back in La Jolla High classrooms.

"To see someplace that's so close to the U.S. which is totally developed, the biggest superpower in the world - to see this place without anything," Kabbage says. "It's shocking." |