|

|

|

Vallarta Living | October 2006 Vallarta Living | October 2006

Day of the Dead: Mexican Festival Celebrates Life Rather than Mourning Deaths of the Departed

Karalee Miller - McClatchy Newspapers Karalee Miller - McClatchy Newspapers

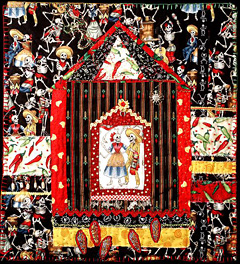

| | Papier-mache skeletons and skulls are used prominently during the holiday to honor the dead. |

Though its name may sound somber and morbid, its purpose is to celebrate and rejoice.

The Day of the Dead - El Dia de los Muertos - is a Mexican festival that honors and remembers loved ones who have died. Mexicans and Mexican-Americans believe that the souls of the deceased return each year to visit them.

Many observers, according to current practice, will spend Nov. 1 - All Saints' Day - remembering deceased children, often referred to as angelitos (little angels), decorating their gravesites with toys and balloons.

On Nov. 2 - All Souls' Day - adults who have died will be honored with homemade altars and displays, lovingly decorated with food, candles and photos.

It's a ritual rooted in tremendous pride. Those who celebrate want to create the most welcoming, pleasant homecoming they can for their departed loved ones and reassure them they will never be forgotten.

"It's not a sad day by any means," says Karla O'Donald, an instructor in the Spanish department at Texas Christian University. "It's a lot of fun."

HOW DO YOU CELEBRATE THE DAY?

People celebrate the holiday in their homes, as well as in cemeteries.

To commemorate the day, families build ofrendas, decorated altars, in honor of the deceased. The altar then is adorned with many gifts, including the favorite food and drink of the deceased and photographs of the loved one. Zenpasuchitl, a type of marigold, is the traditional flower of the occasion and is placed on the altars. Candles are lighted to serve as a guide back home.

Other traditional symbols include pan de muertos - Day of the Dead bread - a loaf made with cinnamon and decorated with "bones" baked specially for the holiday. Papier-mache skeletons and skulls are used prominently during the holiday to honor the dead.

In Mexico, stores sell sugar candy in the shape of skulls, with names written on them, says O'Donald of TCU.

"You buy them with your name on it and then bring it home and put it on the altar," she says. "Then, on the second, you break it - it's a very hard, hard candy - and you eat a piece of it. It's like saying, 'I cheated death because I'm eating you.'"

Also on Nov. 2, family members gather at the gravesites of their loved ones. They decorate the graves with flowers and have picnics, serving the favorite foods of the deceased.

"The whole family sits there and has a meal in their (deceased loved one's) presence, supposedly," O'Donald says. "Some play music . . . some even dance."

Others may participate in an all-night candlelight vigil at the graves. They talk about their lost loved ones with others at the cemetery and remember the times they shared.

WHAT IS THE DAY'S ORIGIN?

The Day of the Dead originally was celebrated through the entire month of August by the Aztecs. When the Spaniards arrived in Mexico in the 1500s, they viewed the ritual as sacrilegious and wanted to make it more Christian. They decided to move the ceremony to coincide with All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day, which is how the holiday came to be celebrated in November.

HOW IS THE DAY DIFFERENT FROM HALLOWEEN?

Though they're often considered one and the same, O'Donald says there are many differences between the two holidays.

"For one, we don't get dressed up," she says of observers of the Mexican holiday. "There's no such thing as going around the neighborhood asking for candy."

The big difference, O'Donald says, is that whereas Halloween is meant to spook, the Day of the Dead is meant to honor.

"It's not scary," she says. "There's no blood, no haunted houses. It's a day to remember." |

| |

|